Über elf Jahre hinweg entstand ´The World Outside´, das neue Album von CEA SERIN – eine Reise durch metallische Klanglandschaften. In unserem Interview spricht Mastermind Jay Lamm über den kreativen Prozess, die Entstehung der Songs, die Arbeit mit Gastmusikern, musikalische Motive und die persönlichen Erfahrungen, die die Texte und Kompositionen geprägt haben.

Das Interview gewährt zudem seltene Einblicke hinter die Kulissen: Wie entsteht ein solch vielschichtiges Album? Wie entscheidet man, wann ein Song „fertig“ ist? Und welche Rolle spielen Dynamik, Atmosphäre und Instrumentation für das Gesamterlebnis? Dieses Gespräch liefert Antworten auf all diese Fragen und lässt die Vision hinter ´The World Outside´ lebendig werden.

Am Ende des Interviews steht der Text außerdem noch in seinem Originalwortlaut auf Englisch.

Jay, wenn Du Dein neues Album ´The World Outside´ als Landschaft beschreiben müsstest, welche Elemente, Farben und Formen würden darin dominieren?

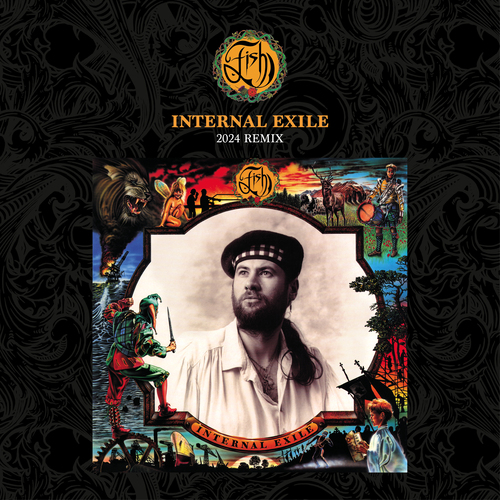

Ich denke, das wird auf dem Albumcover ziemlich gut dargestellt, das speziell mit diesem Gedanken im Hinterkopf gemacht wurde. Mir ist aufgefallen, dass ein Album-Artwork manchmal ein Farbschema hat, und ich kann nicht anders, als diese Farben gewissermaßen zu „fühlen“, während das Album läuft. Zum Beispiel erinnere ich mich, als ich OVERKILLs ´W.F.O.´-Album bekam – es war so ziemlich durchgehend grün und schwarz, und das Album hatte tatsächlich ein fast schimmeliges Grün-Gefühl. Für unser neues Album tendierte ich immer zu Gold und Grau mit rustikalen Brauntönen. Das würde den Eindruck von Sonnenuntergang/Sonnenaufgang vermitteln, während die anderen Farben leicht entsättigt werden, außer der blanken Wand des Innenraums eines Hauses. Es gibt auch ein bisschen Rot, das ich als hoffnungsvoll oder jugendlich betrachtete.

Insgesamt wollte ich dieses Gefühl von Naturfarben vermitteln, um den Titel ´The World Outside´ zu signalisieren. Ein Farbschema, das man bei Sonnenauf- oder -untergang über Weizenfeldern sehen würde, aber betrachtet vom Inneren eines Hauses.

Ich mag es einfach sehr, wenn Alben ein spezifisches Farbschema im Cover und durchgehend haben. Daran denke ich immer, während ich das gesamte Album höre.

Gab es Momente während der elfjährigen Arbeit an diesem Album, in denen Du das Gefühl hattest, dass ein Song oder eine Idee „nicht funktioniert“ – und wie hast Du diese Blockaden überwunden?

Dieses Gefühl bekomme ich nur, während ich am Song arbeite und mit ihm vorankomme. Ich bin an einer Stelle und bekomme dieses Gefühl im Bauch, dass das Riff langweilig ist oder nicht wirklich für sich allein stehen kann. Ich sage mir nie: „Nun, es wird cooler, sobald Keyboard und Bass eingespielt sind.“ Nein, wenn ich dieses kleine Gefühl im Bauch höre, das mir sagt: „Das ist nicht so cool, wie es sein sollte“, dann sammle ich weiter Ideen. Ich möchte, dass die Musik des Songs als Instrumental für sich alleine stehen kann und nicht vom Gesang „gerettet“ werden muss. Typischerweise ist die einzige Ausnahme, wenn ich einen Refrain erarbeite. Größtenteils möchte ich, dass die Musik im Refrain weniger „busy“ ist als die anderen Teile, damit der Gesang wirklich glänzen und die Freiheit haben kann, sich in jede melodische Richtung zu bewegen, die ich vielleicht will. Also halte ich mich im Refrain normalerweise etwas zurück, damit der Gesang der wichtigste Teil sein kann. Für alles andere möchte ich, dass die Musik für sich steht, selbst wenn es ein Instrumental wäre.

Es ist einfach sehr wichtig, auf deine Intuition zu hören. Behebe die Dinge, die nicht funktionieren, sobald du dieses Gefühl bekommst, damit du nicht später zurückgehen und versuchen musst, alles andere um das Problem herum passend zu machen.

Welche Rolle spielten die Gastmusiker wirklich – waren sie eher Mitgestalter oder Spiegel deiner eigenen Vision?

Die Gastmusiker waren sozusagen in zwei Teile gegliedert: Es gab eine Gastsängerin und der Rest waren Gastsolisten. Was Steffi und ihren Part auf ´The Rose On The Ruin´ anging, habe ich ihr im Grunde eine Version des Songs geschickt, in der ich die zweite Strophe singe. Ich sagte ihr, sie könne sie ändern, wenn sie wolle, aber sie sang sie auf die gleiche Weise, wie ich sie ursprünglich hatte. Und dann hat sie in den Refrains einfach meinen Leadgesang gedoppelt, und die Harmonien habe ich selbst gemacht.

Im Grunde waren die Songs vollständig fertig und brauchten nur noch Soli. Also, als es an der Zeit war, ein paar Soli zu bekommen, habe ich eine Reihe von Leuten kontaktiert, von denen ich dachte, dass sie jeweils an den spezifischen Stellen gut funktionieren würden. Größtenteils ließ ich ihnen freie Hand, was die Soli anging. Ich schickte allen ein Video zusammen mit der Musik, um zu verdeutlichen, wo die Dinge hineinpassen würden. Auf dem Video hatte ich Markierungen, wo jedes Solo ist, und ich hatte Notizen auf dem Bildschirm, was ich suchte. Zum Beispiel beginnen viele Soli mit dem, was ich „Thema“ nennen würde, das schließlich in das ausgewachsene „Solo“ übergeht. Manchmal hatte ich das Thema bereits aufgenommen, wollte aber, dass sie es ersetzen und in ihr eigenes Solo einarbeiten, der Kohärenz wegen.

Es gab auch Zeiten, in denen ich wollte, dass das Ende ihres Solos das musikalische Motiv taggt, das direkt nach ihrem Solo kommt. Also sagte ich ihnen, sie sollten ihr Solo mit einem ähnlichen Thema enden lassen, das nach ihrem Solo kommt, um das Element einzuführen, sodass der Song es von dort tragen kann. Oder manchmal wollte ich, dass sie die musikalische Melodie, die vor ihrem Solo kam, in ihr Solo hinübertragen und dann von dort aus weitergehen.

Sie hatten also freie Hand, jedes Solo zu spielen, das sie wollten, aber es gab Teile, bei denen ich die Richtung vorgab, welche musikalischen Motive ich gerne integriert hätte.

Jede der sechs langen Kompositionen ist wie ein kleines Epos. Wie entscheidest Du, wann ein Song „fertig“ ist, wenn man so viele Schichten hinzufügen könnte?

Ich wollte, dass jeder Song wie ein Album für sich klingt. Aber ich beabsichtige nie, dass sie so lang sind. Es ergibt sich einfach so.

Wie ich zuvor angedeutet habe, beginne ich beim Schreiben eines Songs typischerweise immer ganz am Anfang und arbeite mich bis zum Ende vor. Manchmal komme ich auf ein Riff oder etwas, von dem ich einfach weiß, dass es der Refrain sein wird, und ich muss das davor liegende Material schreiben, aber größtenteils fange ich mit dem Intro an und gehe von dort aus weiter.

Tatsächlich ist das der Grund, warum so viele Songs mit einem dieser langen Keyboard-Intros beginnen. Diese Intros sind gewöhnlich einfach ich, wie ich mich hinsetze und etwas am Klavier improvisiere.

Der erste, dritte und vierte Track begannen alle damit, dass ich mich einfach hinsetzte und etwas improvisierte, und dann führte das dazu, dass es ein Song wurde. Die Musik, die Sie am Anfang dieser Songs hören, war das erste Mal, dass ich diese Parts spielte. Manchmal verfeinere ich es ein wenig oder probiere daran herum, aber ich drücke Aufnahme auf meinem Keyboard und nehme auf, was ich tue. Danach kehre ich nie mehr dorthin zurück. Es ist einfach ein im Moment eingefangener Augenblick.

Ich versuche, nicht zu viele Schichten hinzuzufügen, weil all das Zeug schließlich im Mix verloren geht. Wenn man etwas aufnimmt, siedelt jedes Instrument in einem Bereich des Klangspektrums. Bassdrums sind tief, Gitarren sind höher oben usw. Ich benutze die Keyboards, um diese Lücken zu füllen, aber manchmal konkurrieren die Keyboards um Platz im Mix mit den Gitarren oder dem Bass.

Also versuche ich, das zu vermeiden. Allerdings sind diese vergrabenen Teile immer irgendwie ein Segen, denn wenn man das Album beim zehnten Mal mit Kopfhörern hört, hört oder bemerkt man vielleicht etwas, das man noch nie zuvor gehört hat.

Du kombinierst Elemente aus Prog, Metal, New Age und klassischer Musik. Gibt es ein bestimmtes Instrument, das Dir besonders oft als „Schlüssel“ für die Atmosphäre dient?

Was „Atmosphäre“ angeht, denke ich, dass das etwas ist, das für CEA SERIN wichtig ist und uns möglicherweise von anderen trennt. Die Keyboards machen oft Dinge, die ein Live-Keyboarder nicht unbedingt tun wollen würde. Ja, manchmal können die Keyboards sehr geschäftig werden, aber oft benutze ich die Keyboards, um diese Farbwäschen zu machen oder diese langen Strecken von Atmosphäre. Die Keyboards fungieren als Klangtextur oder nehmen den Platz von sonischer Kinematografie ein.

Ich wusste, dass ich niemals einen Live-Keyboarder haben würde, also schrieb ich die Keys so, dass sie entweder sehr dicht und geschichtet oder sehr weit und atmosphärisch sind.

Die Gitarren, der Bass und die Drums sind sicherlich da, um der Metalband-Ästhetik zu dienen, aber die Keyboards sind da, um dieser ganzen Sache eine breite Landschaft zu verleihen. Wenn Gitarren, Bass und Drums die Schauspieler in der Szene sind, dann sind die Keyboards die Bühne und der Horizont.

Gibt es musikalische oder lyrische Motive, die sich wie „geheime Fäden“ durch das ganze Album ziehen?

Eigentlich nicht. Tatsächlich habe ich darüber nachgedacht, es dann aber verworfen, weil ich wollte, dass jeder Song wirklich sein eigenes Ding ist. Beispiel: Als ich ´All The Light That Shines´ schrieb, hatte ich beabsichtigt, dass dieser Song der erste Song ist, einige Themen für den Rest der Songs etabliert und das Riff einführt, das der letzte Song auf dem Album sein würde, der zu diesem Zeitpunkt ´When The Wretched And The Brave Align´ sein sollte. Aber diese beiden Songs funktionierten so gut zusammen, dass ich sie einfach so ließ, wie sie sind.

Ich weiß, dass viele Bands das tun, worüber Du sprichst. Sie rufen bestimmte musikalische Motive und Themen zurück, und der eifrige Hörer wird sie als Rückverweis erkennen. Aber für mich ist jeder Song wirklich sein eigenes Ding, und ich möchte nicht, dass sie auf irgendeine andere Weise miteinander verknüpft sind.

Viele Songs handeln von Widerstand, Selbstbestimmung und innerer Stärke. Gab es persönliche Erfahrungen oder Beobachtungen, die besonders stark in die Texte eingeflossen sind?

Es gab ein paar Dinge. Hauptsächlich frage ich mich, welches Thema ich behandeln möchte, das die Zeit überdauert und auch in Jahrzehnten noch relevant ist. Ich möchte keine Liebeslieder über eine bestimmte Person schreiben oder irgendetwas über irgendeine politische Aussage zu dem, was gerade passiert. Ich möchte über Dinge schreiben, die universeller sind, aber auch mir wichtig.

Damals ging ich durch eine Scheidung, und das, zusammen mit einigen anderen Leuten, die ich im Laufe meines Lebens kannte, beeinflusste ´The Rose On The Ruin´. Der letzte Song auf dem Album, ´Wisdom Of The Aging Fathers´, basierte auf einem Konzept, das ich im Director’s Commentary von „28 Days Later“ gehört habe. Darüber, wie wir im Leben einer Reihe von Vaterfiguren begegnen und wie wir von ihnen lernen und sie übertreffen müssen, um jegliche innere Zerrissenheit über unsere eigenen Kämpfe loszuwerden und zu versuchen, unsere eigene Person zu werden. Ich las auch viel Ayn Rand, was mich ein bisschen beeinflusste, was meine Betonung auf Individualität angeht.

Du arbeitest gerne mit Text-to-Speech und „Brain-Chatter“-Elementen. Welche Geschichten oder Bedeutungen verstecken sich in diesen Schichten, die man auf den ersten Blick nicht hört?

Ja, und genau so nenne ich es immer, „chatter“ – dieses unablässige Geräusch hinten in deinem Kopf, das nicht die Klappe hält. Das ist, wenn ich Zitate aus Filmen nehme oder Text-to-Speech verwende, um einen inneren Dialog zu erschaffen. Hattest Du jemals einen langen Tag, wolltest schlafen gehen und konntest dein Gehirn einfach nicht abschalten? Darum geht es dabei irgendwie.

Als das Album gemischt wurde, wies ich Tom MacLean darauf hin, dass einige Dialogzeilen gerade so weit vergraben sein müssen, dass man fast nicht verstehen kann, was gesagt wird. Es bleibt nur der Eindruck von „chatter“. Es gibt jedoch einige Zeilen, die etwas mit dem Thema des Songs zu tun haben. Offensichtlich ist der Dialog am Anfang von ´All The Light That Shines´ wichtig. Zeilen wie „you have a duty to live“ sind wichtig. Dinge, die herausstechen und offensichtlich sind, sind immer irgendwie relevant gemeint.

Aber das kann von innerem Hirn-Geplapper bis zu Dingen reichen, die man andere Leute neben einem auf der Straße sagen hört, oder sogar eine Zeile aus einem Buch, die für das Thema relevant ist. Manchmal mag ich einfach die emotionale Darbietung einer Zeile; das Dampfablassen.

Ich benutze es gerne als eine Art dynamischen Postskript, nachdem der Gesang und die Texte einen gewissen Punkt erreicht haben, an dem sie geruht haben.

Wenn Du einen Songtext aus ´The World Outside´ in ein Bild oder eine Szene im echten Leben übersetzen würdest – welche wäre das?

Ich habe versucht, das mit dem inneren Album-Artwork zu tun, aber da ich begrenzte Mittel hatte, konnte ich es nicht wirklich perfekt erreichen. Zuerst dachte ich daran, KI zu benutzen, um den Punkt wirklich rüberzubringen, aber ich wusste, dass die Leute austicken würden, wenn ich KI im Album-Artwork verwenden würde. Also habe ich die gesamte Fotografie selbst gemacht. Aber beim ersten Song, ´Where None Shall Follow´, wollte ich wirklich etwas haben wie das, was im Album-Booklet ist, aber anstelle der einsamen Person, die mit einem Koffer auf einen hellen Horizont zugeht, wollte ich diese lange, lange Reihe von Menschen, die die gleiche Art von Kleidung tragen, in die gleiche Richtung gehen, und dann eine Person, die aus dieser Reihe tritt und ihren eigenen Weg einschlägt.

Du hast großen Wert auf Dynamik gelegt, statt auf Lautstärke und „Loudness Wars“. Welche Herausforderungen stellten sich bei der Mischung der vielen Instrumente und Schichten?

Für den Fall, dass andere Leute noch nie davon gehört haben: Die „Loudness Wars“ ist ein Begriff, der sich auf moderne Mixing- und Mastering-Techniken bezieht, um die Alben so laut wie möglich zu machen, ohne zu clippen und zu verzerren. Wenn Du ein Album aus den 80ern hörst und ein modernes Album, kannst Du erkennen, wie dramatisch der Unterschied in den Lautstärkepegeln ist. Ein lautes und knallendes Metalalbum zu machen klingt für bestimmte Bands cool, aber man verliert auch Dynamik, weil die Kompression alle leisen Teile anhebt und die lauteren Teile niederdrückt. Es macht das visuelle Äquivalent eines Audio-Ziegels, bei dem es keine echten Spitzen und Täler des Dynamikumfangs gibt, nur einen großen Klangblock.

Wenn Du nun ein klassisches Album hörst, wirst du bemerken, dass du zum Lautstärkeregler greifst, um aufzudrehen, wenn die Musik sehr leise wird.

Das fehlt in modernen Metal-Produktionen. Wir haben versucht, ein glückliches Mittel zu finden, ein modern klingendes Metal-Album zu bekommen, aber auch den leiseren und schöneren Teilen gerecht zu werden.

Es war tatsächlich eine ziemliche Herausforderung. Wie ich zuvor sagte, siedelt jedes Instrument in einem bestimmten Bereich des Klangspektrums, daher ist es bereits schwierig, Dinge hörbar zu machen, wenn mehrere Instrumente und Sounds um den gleichen Raum konkurrieren.

Aber ich denke, wir konnten eine schöne Balance im Mix erreichen, sodass es in Deinem Auto großartig klingt – und wenn Du es mit Kopfhörern hörst, wirst Du noch so viel mehr entdecken können.

Die Schwierigkeit bei der Anpassung an die Dynamik besteht darin, dass man einige Kompromisse eingehen muss. Willst Du ein knallendes Metal-Album? Oder willst Du ein dynamisch klingendes Album mit vielen Höhen und Tiefen? Für mich wollte ich, dass die leiseren Teile tatsächlich traurig und ein bisschen unterdrückt klingen, damit es, wenn es wieder einsetzt, viel mehr Wucht hat. Ich wollte die Leute nicht zum Lautstärkeregler greifen lassen, aber ich wollte auch nicht diese .WAV-Wellenform-Audiodatei, die wie eine Backsteinwand aussieht – einfach superkomprimiert über die gesamte Bandbreite. Das wollte ich absolut nicht.

Also ja, wir sind eine ganze Weile hin und her gegangen, um das genau richtig einzustellen.

Manche Passagen wirken wie ein Dialog zwischen den Instrumenten. Gab es Momente, in denen Du die Musik einfach „sprechen“ lassen wolltest, ohne Gesang?

Oh, absolut. Tatsächlich – zitiere mich nicht – aber ich denke, vielleicht sind 75 % des Albums instrumental. Ich weiß nicht, vielleicht 70 %. Wie auch immer, der Punkt ist: Die Musik sollte immer für sich stehen. Tatsächlich habe ich jahrelang mit diesen Songs als Instrumentals gelebt und hatte die Melodien nur in meinem Kopf. Ich fuhr herum und hörte mir die Songs als Demos nur als Instrumentals an, machte mir in meinem Kopf Notizen, welche Änderungen vorgenommen werden müssen, wo welche Soli hin sollten, welche Art von Versgesang es geben sollte usw.

Und was den Dialog zwischen Instrumenten angeht, ja, das mache ich die ganze Zeit. Ich erinnere mich, dass ich bemerkte, wie in Beethovens 5. Symphonie dieses berühmte Eröffnungsriff, das wir alle kennen, wiederholt wird, aber auf verschiedenen Instrumenten. Also hatte ich das immer im Kopf als etwas Cooles, das man von Zeit zu Zeit tun kann. Eine Gitarre startet ein Riff, die Keyboards nehmen die nächste Runde, dann lassen die Streicher es wiederholen. Solche kleinen Dinge mochte ich immer, um das Erwartete aufzubrechen.

Welche Entscheidungen bei den Soli und Instrumentalparts waren am kontroversesten – und wie hast Du Dich entschieden, welche Version bleibt?

Nichts allzu Großes. Ich erinnere mich, dass es diesen Turnaround-Abschnitt in ´Where None Shall Follow´ gab, der zurück in den letzten Refrain führte und der viel Herumprobieren erforderte. Ich schrieb immer wieder verschiedene Wege, um zurück in den Refrain zu kommen. Als Keith Warman in der Band war, machte er die Bemerkung, dass ich, wann immer ich dachte, dass etwas nicht funktionierte, dazu tendierte, „mehr hinzuzufügen“, während ich eher darüber nachdenken sollte, „wegzunehmen“. Ich denke, das war größtenteils ein guter Rat. Ich glaube, das resultierte in dem, was wir jetzt auf dem fertigen Album haben.

Es gab ein Filmsample, das ich herauszunehmen beschloss. Es gab eine Zeile, die ich aus dem ersten Harry-Potter-Film genommen hatte: „Clearly, fame isn’t everything.“ Ich meine, diese Zeile bezog sich speziell auf das Thema des Songs und passte perfekt; allerdings ist die Zeile und der Schauspieler, der sie liefert, inzwischen so auffällig, dass ich dachte, es würde den Song überschatten. Ich ließ „clearly“ drin, aber schnitt den Rest heraus.

Ich zerhacke manchmal auch die Dialog-Samples. Manchmal schneide ich alberne Wörter oder eine Phrase heraus. Aber meistens sind sie da, weil mir der Klang der Stimme gefällt und die Darbietung des Schauspielers und die Emotion dahinter zu dem passt, was ich möchte, dass die Leute fühlen.

Aber größtenteils gab es nie irgendwelche Streitereien oder Kontroversen über Parts. Schließlich zeige ich der Band nie wirklich, woran ich arbeite, bis es fertig ist. Und normalerweise, sobald der Song fertig ist, sind alle glücklich.

Es gab jedoch dieses eine Mal: Auf dem zweiten Album gibt es einen Song namens ´The Victim Cult´ und Keith mochte ihn einfach nie. Ich versicherte ihm immer wieder, der Song würde cool sein, sobald alle Parts aufgenommen wären. Das war ein seltsamer Song und musste wirklich bis zum Ende durchgezogen werden, um das volle Bild davon zu bekommen, wie er am Ende klingen sollte.

Wenn Du das Album einem Hörer beschreiben müsstest, der noch nie Prog Metal gehört hat – welche drei Bilder, Gefühle oder Erfahrungen würdest Du nennen?

Die Szene oder das Bild einer Person, die sich selbst aus einer tiefen, dunklen Grube herauszieht, nur um nach oben zu schauen und festzustellen, dass es noch eine weitere Felswand gibt, die es zu erklimmen gilt. Also holt die Person Luft, gibt sich selbst eine Sekunde, um die eigenen Gedanken zu sammeln, macht sich bereit und beginnt den nächsten Aufstieg, im Wissen, dass auch dies bezwungen werden wird.

Das Gefühl, auf einer belebten Autobahn zu sein, dein Auto trifft eine schmierige Stelle auf der Straße und gerät ins Schleudern – aber dann bekommst du es wieder unter Kontrolle. Dein Herz rast, aber du fühlst dich wie ein Badass, weil du das Chaos im Griff behalten hast.

Und wenn Popmusik ein Teller mit gemischten, unverpackten Süßigkeiten ist, dann ist Prog Metal ein Manhattan-Cocktail in einem verschlossenen Safe.

Du nennst YANNI und LORD BANE als Einflüsse. Welche Aspekte ihrer Musik haben Dich diesmal am stärksten inspiriert, und wie fließen sie in das Album ein?

Ja, LORD BANE war ein riesiger musikalischer Einfluss auf mich. Einfach alles an ´Age Of Elegance´ hat mich begeistert, als ich aufwuchs und lernte zu spielen. Besonders die Keyboards auf diesem Album. Die Keyboards haben die Gitarren nicht gedoppelt, sie waren nicht super geschäftig, es waren nicht diese klischeehaften Sounds. Wenn die Gitarren melodisch nach unten gingen, gingen die Keyboards nach oben; wenn die Gitarren beschäftigt waren, machten die Keyboards diese weit schweifenden Klangwäschen. Die Keyboards auf diesem Album waren einfach so einzigartig. Der Gesang war phänomenal und die Drums waren ebenfalls so einzigartig, mit der Einbindung von militärischen Snare-Linien hier und da. Es war einfach so cool.

Yanni war auch immer ein großer Einfluss für mich. Ich habe mit Klavier angefangen Musik zu machen, also habe ich eine Schwäche für Sachen wie Yanni, Hania Rani und Ludovico Einaudi. Der größte Einfluss auf mich in Bezug auf Yanni und wie es sich auf Metal bezieht, war das Songwriting und die Struktur der Songs von seinen Live-Alben. Das war damals, als er viele seiner Songs verändert hat, um mit einer großen Liveband während dieser ´Live At The Acropolis´- und ´Tribute´-Shows zu funktionieren. Wenn du diese Alben hörst, wirst du einfach eine Menge Soli von so vielen verschiedenen Arten von Instrumenten und Spielern aus der ganzen Welt hören. Es gibt so viele Stile und Texturen, die in diese Songs geworfen werden. Es ist einfach wirklich interessant, zuzuhören. Ich liebe diese Alben immer noch.

Du kannst auch hören, wie ich seine musikalischen Motiv-Übergabe-Tricks verwende. Ich habe das vorher ein bisschen früher erwähnt. Nehmen wir an, es gibt ein Basssolo, das in den nächsten musikalischen Teil und die Melodie führt. Mir fiel auf, dass ein Solo manchmal mit einem Hinweis auf das kommende Melodiethema endet. Es ist ein wunderschöner Trick aus Kohäsion und Mustern.

Wenn Du ´Until The Dark Responds´ und den großen Abschnitt in diesem Song hörst, in dem alle Soli aufeinander losgehen, ist das ein direkter Einfluss von Yanni.

Wenn ´The World Outside´ als „Zeitmaschine“ funktionieren könnte – welche Epoche oder welche Stimmung würdest Du dem Hörer vermitteln wollen?

Hoffentlich wird es nicht in einer Epoche eingeschlossen sein. Ich bin sicher, manche Leute würden es hören und sagen, es klinge irgendwie 80er-mäßig mit der Gitarrenarbeit und so, aber für mich würde ich hoffen, dass es für sich steht. Ich würde gern denken, dass die Leute dieses Album in 20 Jahren immer noch hören können und das Gefühl haben, dass es relevant klingt.

Was den Geisteszustand angeht, denke ich, dass er am besten in der allerletzten Minute von ´Where None Shall Follow´ zusammengefasst werden kann. Das Ende dieses Songs, aus dem Refrain und all der Schwere herauskommend und dann auf dem schönen Klavier- und Streichpart endend… Ich würde gern denken, dass das die Stimmung des Albums verkapselt. Dieses Gefühl, etwas Schwieriges und Intensives durchgemacht zu haben, um auf der anderen Seite als stärkerer Mensch mit einem Gefühl von Hoffnung und Erfolg hervorzugehen.

Nach elf Jahren Arbeit – gibt es musikalische Ideen, die es nicht aufs Album geschafft haben, die Du aber irgendwann in der Zukunft verwirklichen willst?

Nicht wirklich. Alle Parts und Abschnitte wurden speziell für jeden Song geschrieben. Damit meine ich, ich hatte nicht einen Haufen Riffs übrig. Ich schrieb Riffs und Akkorde und Melodien speziell für jeden Song. Welche neuen Riffs auch immer ich jetzt vielleicht ausarbeite, sind für andere Dinge in der Zukunft.

Nicht nur das, sondern als ich mit dem Schreiben der Musik für ´The World Outside´ fertig war, ging ich tatsächlich zu anderen Dingen über. Ich wartete tatsächlich darauf, dass Keith Warman seine Gitarrenparts aufnimmt. Also, während ich darauf wartete, dass er das macht, begann ich, an Musik für ein paar andere Projekte zu arbeiten. Ich bin zu diesen anderen Projekten zurückgekehrt, um sie abzuschließen. Es wird nicht CEA SERIN sein, sondern neue Bandnamen und neue Projekte, im Grunde unter einem neuen Banner.

Was bedeutet Dir persönlich der Abschluss dieses Albums – als Musiker, als Komponist, als Mensch?

Ich erzähle Dir eine Geschichte darüber, wie lange diese Songs in meinem Kopf darauf gewartet haben, endlich von anderen gehört zu werden.

Im Jahr 2004 habe ich meinen ersten Deal mit „Heavencross Records“ für Europa und „Nightmare Records“ in den USA unterschrieben. Nachdem ich diese Verträge unterschrieben hatte, sprach ich mit meiner Mutter darüber, was da alles los war. Sie fragte mich, wie der Name unseres zweiten Albums sein würde, und ich sagte: ´The World Outside´. Also, das war 2004, dass ich wusste, dieses Album ist in Arbeit. Ich hatte die frühesten Stadien der Songs schon damals in Entwicklung. Ich hatte den Albumnamen schon damals. Also ja, ein wenig über 20 Jahre habe ich darauf hingearbeitet, dieses Album fertigzustellen.

Im Januar 2025 war ich es einfach leid, auf andere Leute zu warten, und beschloss, es selbst zu machen. Natürlich hat Rory alle Drums und Percussion gemacht, aber ich entschied, das Album zu Ende zu bringen, indem ich die Gitarren selbst aufnahm und die Soli an andere vergab. Es war eine harte Entscheidung, aber eine notwendige.

Der Tag, an dem ich alle einzelnen Spuren heruntergemischt und sie alle an Tom MacLean übergeben habe, damit er den finalen Mix und das Master macht… das war die beste Schlafnacht, die ich in zwei Jahrzehnten hatte.

Das Album und der Computer, auf dem es war, hatten eine Überschwemmung überlebt. Als mein Haus mit mehreren Fuß Flusswasser überflutet wurde, hatte ich dafür gesorgt, den Computer und die Backups zu retten. Es war das Wichtigste für mich, es zu retten.

Ich bin enorm stolz auf dieses Album, und wenn ich sterbe, wäre ich glücklich, wenn „Bekannt für das Album ´The World Outside´ von CEA SERIN“ auf meinem Grabstein stünde. Damit meine ich: Wenn ich morgen sterbe, kann ich zumindest sagen, dass ich dieses Projekt endlich bis zum Ende gesehen habe und es so herauskam, wie ich es wollte. Es ist meine stolzeste Leistung und mein Lieblingsding, das ich getan habe… bis jetzt.

Wenn jemand ´The World Outside´ in zehn Jahren noch einmal hört – welche Entdeckung soll er diesmal machen, die er beim ersten Hören noch nicht bemerkt hat?

Zwei Dinge:

Ein Freund sagte mir einmal, sein Vater habe diese Idee gehabt, dass, wenn eine Person ein Musikstück hört und in der Lage ist, jede Note zu hören und jedes Detail zu bemerken, sie dann von diesem Zeitpunkt an jegliches Interesse an diesem Musikstück verloren haben würde. Ich stimme dem nicht unbedingt zu, aber ich mag das Gefühl, dass ein Musikstück dem Hörer eine Tiefe der Entdeckung bieten muss, die über Jahre hinweg „Belege“ liefert.

Das zweite ist, dass ich ein Video auf YouTube gesehen habe von jemandem, der ein paar Progressive-Metal-Alben auflistete, die vor 20 Jahren herauskamen, aber heute immer noch relevant klingen. Unser erstes Album stand auf dieser Liste.

Also hoffe ich, dass die Leute dieses Album ein Jahrzehnt von jetzt an hören, immer noch neue Details entdecken und immer noch denken, dass es relevant klingt und nicht ära-spezifisch, d. h. nicht nach 80ern oder 90ern klingend.

Obendrein hoffe ich, dass die Leute sehen und hören werden, dass die lyrischen Themen immer noch relevant sind und es immer sein werden, d. h. die dargestellten Ideen über Kampf, Individualität, Ziele erreichen und das Licht tragen, damit andere den Weg sehen.

Jeder Track auf ´The World Outside´ fühlt sich an wie ein eigenes Kapitel. Gibt es eine verborgene Dramaturgie, die die Stücke zu einer größeren Geschichte verbindet?

Nein, jeder Song ist seine eigene Geschichte, seine eigene Entität und thematisch nicht miteinander verbunden. Die letzten drei Songs verbinden sich ohne Unterbrechung, aber die lyrischen Themen sind unterschiedlich. Es ist sicherlich kein Konzeptalbum wie ´Operation: Mindcrime´ und kein Konzeptalbum mit einem übergreifenden verbindenden Gewebe.

Tatsächlich ist das irgendwie der Grund, warum ich diese längeren Intros bei manchen Songs mag, um als “Gaumenreiniger” von dem letzten Song zu dienen, den sie vielleicht gehört haben. Es ist wie die Eröffnungscredits des nächsten Films.

Manche Songs scheinen inneren Konflikt einzufangen, während andere wie Aufbruch und Befreiung klingen. Spiegelt das eine persönliche Reise wider oder eine eher universelle Erfahrung?

Alle Songs sind definitiv aus persönlicher Erfahrung und Beobachtung abgeleitet, aber so geschrieben, dass sie universeller sind.

Ich habe sicherlich meine eigene Sicht und Erfahrung damit, zu versuchen, meinen eigenen Weg zu gehen, wie in ´Where None Shall Follow´ behandelt. Ich habe Menschen kennengelernt und emotionale Verbindungen zu den Personen, die die Ruhmsuchenden, nach sofortiger Befriedigung strebenden Horden in ´The Rose On The Ruin´ beeinflussten. Ich habe meine eigenen Bestrebungen und Interessen und kann sehen, wo ich angefangen habe und wo ich derzeit bin, wie in ´Until The Dark Responds´ diskutiert, aber ich kann auch sehen, wie es sich im größeren Maßstab auf die Menschheit bezieht. Und was ´All The Light That Shines´ und ´When The Wretched And The Brave Align´ angeht, denke ich, dass wir alle unsere eigenen Erfahrungen teilen können und in der Lage sind, uns mit unseren eigenen Geschichten in Bezug auf Führung durch Vorbild und wie man mit Konflikten umgeht, gegenseitig zu verbinden. Schließlich habe ich bei ´Wisdom Of The Aging Fathers: Three Regards To Reason´ meine eigenen drei Vaterfiguren kennengelernt, von ihnen gelernt und habe das Gefühl, dass ich dank ihrer Führung meinen eigenen Weg geschmiedet habe, und ich denke, andere werden ihre eigene ähnliche Reise in Bezug auf dieses Thema haben.

Gibt es eine Figur, ein lyrisches „Ich“ oder eine Stimme, die sich durch das Album zieht – oder ist jeder Song eine neue Perspektive?

Ich denke nicht, dass es ein lyrisches „Ich“ im gesamten Album gibt. Vielleicht im Sinne davon, dass es einen einzelnen Schauspieler gibt, der verschiedene Charaktere darstellt – um eine filmische Referenz zu verwenden. Es ist die gleiche Person, die wir kennen und erkennen, aber die Figur, die sie diesmal spielt, ist eine andere. Oder vielleicht ist es wie die Abendnachrichten, und wir sehen all diese verschiedenen Nachrichtenmeldungen. Es sind alles unterschiedliche Geschichten, alles unterschiedliche Ereignisse, aber alle erkennen die Stadt oder den Ort, an dem sie stattfinden.

Einige Stücke haben Passagen, die fast wie „innere Monologe“ wirken. Hast Du bewusst mit dem Gedanken gespielt, Musik als Sprache des Unterbewusstseins einzusetzen?

Ich denke, vielleicht ist Musik eine Reaktion auf das Unterbewusstsein, eine Reaktion auf das, womit das Unterbewusstsein zurechtkommt, oder eine Übersetzung von Emotion in Gedanken, wenn das Sinn ergibt.

Ich weiß, dass es viele Male vorgekommen ist, dass ich etwas gesehen habe, etwas gehört habe, von etwas bewegt wurde und dann – mit dieser inneren Emotion aufgewühlt – einige musikalische Elemente in meinem Kopf auftauchten.

Ich denke, es ist die Pflicht eines jeden Musikers, sein Instrument und seine Stimme in einem solchen Maße zu lernen, dass er das, was er in seinem Kopf hört, wenn er so aufgewühlt wurde, manifestieren kann.

Wenn Du einen Song als „Schlüssel“ zum ganzen Album wählen müsstest – welcher wäre es, und was offenbart er?

Das wäre ´Until The Dark Responds´, das sich direkt auf viele der Themen bezieht sowie auf das Album-Artwork. Es stellt direkt in Frage, was die Leute Dir vielleicht erzählen, wie die Welt da draußen auf eine bestimmte Weise sei, aber wenn Du selbst einen Blick darauf wirfst, wirst Du sehen, dass die Leute vielleicht eher versuchen, Dich dazu zu bringen, die Dinge auf ihre Weise zu sehen und nicht auf Deine eigene. Vor diesem Hintergrund geht es in ´Until The Dark Responds´ darum, in dieser Welt zu leben, in der die Menschen um einen herum versuchen, einen bei der Verfolgung seiner Ziele und Ambitionen in die Irre zu führen. Es könnte auch ein Spiegel der Evolution der Menschheit sein und ein Zeugnis dafür, wie weit wir gekommen sind.

Ich denke, wir sollten immer für unsere Ziele, Zwecke und Ideale kämpfen. Egal, was irgendjemand dir sagt. Im Leben werden wir zu Boden geschlagen, wir werden sogar getreten, während wir unten sind, wir werden verspottet und verhöhnt. Aber es gibt eine Binsenweisheit, an die ich immer festhalten werde: „Es kommt nicht darauf an, was sie sagen, sondern was du weißt.“

Immer wieder aufstehen. Denn Leiden gehört zum Weg dazu. Aber es definiert dich nicht. Niedergeschlagen zu werden ist eine Gewissheit. Was zählt, ist, wieder aufzustehen und deine Würde und deinen Verstand zu bewahren. Denn diejenigen, die ihre Träume verwirklichen, sind nicht diejenigen, die niemals scheitern, sondern diejenigen, die sich weigern, am Boden zu bleiben. Also mach weiter, kämpfe weiter. Streb weiter. Bis zu deinem letzten Atemzug – und bis die Dunkelheit antwortet.

https://generationprog.bandcamp.com/album/the-world-outside

https://www.facebook.com/CeaSerinMusic

English-Version:

If you had to describe ´The World Outside´ as a landscape, what elements, colors, and shapes would dominate it?

I think it’s pretty well represented on the album cover which was specifically made with that in mind. I’ve noticed that sometimes an album’s artwork has a color scheme to it, and I can’t help but sort of “feel” those colors as the album goes on. For example, I remember when I got OVERKILL’s ´W.F.O.´ album, it was pretty much green and black throughout, and the album did have an almost moldy green feel to it. For our new album, I was always leaning towards gold and grey with rustic browns. That would give the impression of sunset/sunrise, while desaturating the other colors slightly except for the bare wall of a house’s interior. There’s also a bit of red throughout as well which I viewed as hopeful or youthful.

Overall, I wanted to put out that feeling of nature’s colors to signify the title of ´The World Outside´. A color scheme you would see at sunrise or sunset over fields of wheat but when looked at from the interior of a house.

I just really like it when albums have a specific color scheme in the cover art and throughout. I always think of that while listening to the entire album.

During the eleven years of working on this album, were there moments when you felt a song or idea “wasn’t working” – and how did you overcome those blocks?

I only get that feeling while I’m working on the song and moving forward with it. I’ll be at a part and just get this feeling in my gut that the riff is boring or can’t really stand on its own. I never say to myself, “well, it’ll get cooler once the keyboard and bass are laid down.” No, if I hear that little feeling in my gut that’s telling me, “this isn’t as cool as it should be” then I keep brainstorming ideas. I want the music of the song to be able to stand on its own as an instrumental and not be “saved” by the vocals. Typically, the only exception for this is when I’m coming up with a chorus. For the most part, I want the music in the chorus to be less “busy” than the other parts so the vocals can really shine and have the freedom to move in any melodic direction I may want. So, I usually lay back a bit in the chorus to allow room for the vocals to be the most important part. For everything else, I want the music to stand on its own even if it were an instrumental.

It’s just very important to listen to what your own intuition is telling you. Fix the stuff that isn’t working as soon as you get that feeling so you don’t have to go back and try to make everything else work around the problem.

What role did the guest musicians really play – were they co-creators, or more like mirrors of your vision?

So, the guest musicians were kind of in two parts: there was one guest vocalist and the rest were guest soloists. When it came to Steffi and her part on ´The Rose On The Ruin´, I basically sent her a version of the song with me singing the second verse. I told her she could change it if she wanted but she sang it the same way I originally had it. And then she just doubled my lead vocal in the choruses and I did the harmonies myself.

Basically, the songs were completely finished and just needed solos. So, when that time came to get some solos, I reached out to a bunch of people that I thought would work well in each specific part. For the most part, I let them do whatever they wanted to do as far as soloing goes. I did send everyone a video along with the music to help illustrate where things were going to fit in. On the video I had indicators on where each solo was at, and I had notes on the screen of what I was looking for. For example, many solos start off with what I would call a “theme” which would eventually lead into the full blown “solo.” Sometimes I would have the theme already recorded but I just wanted them to replace and incorporate it into their own solo for the sake of sounding cohesive.

There were also times when I wanted the end of their solo to tag the musical motif that comes right after their solo. So, I would tell them to end their solo with a similar theme that comes after their solo to introduce the element so the song can carry it from there. Or sometimes I would want them to take the musical melody that came before their solo, carry it over into their solo, and then go from there.

So, they had free reign to do whatever solo they wanted but there were parts where I gave direction on which musical motifs I would like incorporated.

Each of the six long compositions feels like a small epic. How do you decide when a song is “finished,” knowing you could keep adding layers?

I did want each song to sound like an album on its own. But I never intend for them to be as long as they are. It just kind of works out that way.

As I hinted at before, when I write a song I typically always start at the very beginning and work my way through to the end. Sometimes I’ll come up with a riff or something that I just know will be the chorus and I have to write the stuff before it, but for the most part I start off with the intro and go from there.

In fact, that’s why so many songs start off with one of those long keyboard intros. Those intros are usually just me sitting down and improvising something on piano.

The first, third, and fourth tracks all started off with me just sitting down and improvising something and then that led into it becoming a song. So, the music you hear at the beginning of those songs was the first time I played those parts. Sometimes I’ll refine it a bit or mess around with it a bit, but I hit record on my keyboard and record what I’m doing. After that, I never revisit it. It’s just a moment captured in time.

I try not to add too many layers because all that stuff will eventually get lost in the mix. When you record something, every instrument resides on this area in the sonic spectrum. Bass drums are low, guitars are higher up, etc. I use the keyboards to fill those gaps but sometimes the keyboards will compete for space in the mix with the guitars or bass.

So, I try to avoid that. However, those buried parts are always kind of a blessing because when you listen to the album a 10th time on headphones you might hear something or notice something you’ve never heard before.

You combine elements of prog, metal, new age, and classical music. Is there a particular instrument that most often serves as the “key” to setting the atmosphere?

As far as “atmosphere” goes, I think that is something that is important to CEA SERIN and something that possibly separates us from others. The keyboards are often doing something that a live keyboardist wouldn’t want to do necessarily. Yes, sometimes the keyboards can get very busy, but a lot of times I’m using the keyboards to make these washes of color or these long stretches of atmosphere. The keyboards will act as sound texture or takes the place of sonic cinematography.

I knew I would never have a live keyboardist so I always wrote the keys to either be very dense and layered or very spacey and atmospheric.

The guitars, bass, and drums are certainly there to serve the purpose of the metal band aesthetic, but the keyboards are there to add this broad range of landscape to everything. If the guitars, bass, and drums are the actors in the scene, then the keyboards are the stage and horizon.

Are there musical or lyrical motifs that act like “hidden threads” running throughout the album?

Actually, there’s not. In fact, I thought about doing that but decided against it because I wanted every song to really be its own thing. Case in point, when I wrote ´All The Light That Shines´ I had intended for that song to be the first song, have it establish some themes throughout the rest of the songs, and introduce the riff that would be the last song on the album which, at that time, was going to be ´When The Wretched And The Brave Align´. But those two songs worked so well together I just kept them the way they are.

I know that many bands do what you’re talking about. They call back certain musical motifs and themes and the avid listener will recognize them as a callback. But, for me, each song is really its own thing and I don’t want them to be linked in any other way.

Many songs deal with resistance, self-determination, and inner strength. Were there personal experiences or observations that strongly shaped the lyrics?

There were a few things. Mainly I ask myself what topic do I want to cover that will stand the test of time and still be relevant decades from now. I don’t want to write love songs about a certain person or write anything about any political statement on what’s going on at the time. I want to write about things that are more universal but also important to me.

At the time, I was going through a divorce so that, along with some other people I knew throughout my life, influenced ´The Rose On The Ruin´. The last song on the album, ´Wisdom Of The Aging Fathers´ was based on a concept that I heard discussed on the 28 Days Later director’s commentary. About how we encounter a number of father figures in our life and how we need to learn from them and surpass them to get rid of any inner turmoil about our own struggles in an effort to become our own person. I was also reading a lot of Ayn Rand which influenced me a bit when it comes to my emphasis on individuality.

You often use text-to-speech and “brain-chatter” elements. What kinds of stories or meanings are hidden in these layers that listeners might not catch at first?

Yes, and that’s how I always put it, “chatter”—that incessant noise in the back of your head that won’t shut up. This is when I take quotes from movies or use text-to-speech to create an inner dialogue. Have you ever had a long day, tried to go to sleep, and just couldn’t shut off your brain? That’s kind of the point of all that.

When the album was being mixed, I pointed out to Tom MacLean that some lines of dialogue need to be buried just enough so that you can almost not make out what is being said. Only the sense of chatter remains. However, there are some lines which have something to do with the topic of the song. Obviously, the dialogue at the beginning of ´All The Light That Shines´ is important. Lines like “you have a duty to live” are important. Things that stick out and are obvious are always meant to be relevant somehow.

But it can range from inner brain chatter to things you might hear other people say on the street next to you, or even a line from a book that is pertinent to the topic. Sometimes I just like the emotional delivery of a line; the venting.

I like using it as a dynamic post-script in a way after the vocals and lyrics have rested a certain point.

If you could translate one song lyric from ´The World Outside´ into a real-life image or scene – what would it be?

I tried to do that with the inner album artwork but since I had limited resources I wasn’t really able to achieve it perfectly. At first, I thought about using AI to really get the point across but I knew people were going to flip out if I used AI in the album art. So, I did all the photography myself. But, the first song, ´Where None Shall Follow´, I really wanted to have something like what is in the album booklet but instead of the lone person walking with a suitcase towards a bright horizon, I wanted this long, long line of people, wearing the same type of clothes, heading in the same direction, and then one person choosing to step out of that line and head down their own path.

You put a strong emphasis on dynamics rather than loudness and the “loudness wars”. What challenges did you face balancing so many instruments and layers?

So, in case other people have never heard of it, the “loudness wars” is a term that references modern mixing and mastering techniques to make the albums as loud as possible without clipping and distorting. If you listen to an album from the 80s and you listen to modern albums you can tell just how dramatic a difference is in the volume levels. Making a loud and slamming metal album sounds cool for certain bands, but you also lose dynamics because the compression is boosting all the quiet parts and squashing down the louder parts. It makes the visual equivalent of an audio brick where there’s no real peaks and valleys of dynamic range, just a big block of sound.

Now, if you listen to a classical album, you’ll notice yourself reaching for the volume knob to turn things up when the music gets very quiet.

That’s missing in modern metal productions. We tried to find a happy medium of getting a modern metal sounding record but also doing justice to the quieter and prettier parts.

It was quite the challenge, actually. As I was talking about before, each instrument resides in a certain area of the sonic spectrum, so it’s already difficult to get things audible when multiple instruments and sounds are competing for the same space.

But I think we were able to achieve a nice balance with the mix so that it sounds great in your car, but when you listen to it on headphones you’ll be able to hear so much more.

The difficulty in adjusting for dynamics is that you have to make some compromises. Do you want a slamming metal record? Or do you want a dynamic sounding album with lots of ups and downs? For me, I wanted the quieter parts to actually sound sad and suppressed a bits so when it kicks back in it has much more impact. I didn’t want to make people reach for their volume knob, but I also didn’t want that .WAV form audio file that looks like a brick wall, just super compressed across the board. I absolutely didn’t want that.

So, yeah, we went back and forth for quite a while trying to dial this in just right.

Some passages feel like a dialogue between instruments. Were there moments when you wanted the music to “speak” on its own, without vocals?

Oh, absolutely. In fact—don’t quote me on this—but I think maybe 75% of the album might be instrumental. I don’t know, maybe 70%. Anyways, the point is, the music should always stand on its own. In fact, I lived with these songs for years as instrumentals and only had the melodies in my head. I would drive around listening to the songs as demos as just instrumentals, making notes in my head of what changes need to be made, what solos should go where, what type of verse vocals there should be, etc.

And as far as a dialogue between instruments, yeah, I do that all the time. I remember noticing how during Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, that famous opening riff we all know, how that’s repeated but on different instruments. So, I’ve always had that in my head as a cool thing to do from time to time. Have a guitar start a riff, have the keyboards take the next rotation, then have the strings repeat it again. I always liked little things like that to break up what’s expected.

Which decisions about solos or instrumental parts were the most controversial – and how did you decide which version stayed?

Nothing too big. I remember there was this turn-around section on ´Where None Shall Follow´ which led back into the last chorus that took a lot of messing with. I kept writing different ways to get back into the chorus. Back when Keith Warman was in the band he made a remark that whenever I thought something wasn’t working, I tended to “add more” when I should think about “taking away.” I think that was good advice for the most part. I think that resulted in what we now have on the finished album.

There was one movie sample I chose to edit out. There was a line I took from the first Harry Potter movie, “Clearly, fame isn’t everything.” I mean, that line specifically related to the topic of the song and fit perfectly; however, the line and the actor who delivers it, is so noticeable now that I thought it would overshadow the song. I left in “clearly” but cut out the rest.

I sometimes chop up the dialogue samples, too. Sometimes I’ll cut out goofy words or a phrase. But mostly they’re there because I like the sound of the voice and the actor’s delivery and the emotion behind it matches what I want people to feel.

But, for the most part, there’s never been any arguing or controversy over parts. After all, I never really show the band what I’m working on until it’s finished. And usually once the song is done everyone is happy.

There was this one time, however, on the second album there’s a song called ´The Victim Cult´ and Keith just never liked it. I kept assuring him the song would be cool once all the parts were recorded. That was a weird song and really had to be seen through till the end to get the full picture of how it was supposed to sound in the end.

If you had to describe the album to someone who has never heard prog metal – what three images, feelings, or experiences would you give them?

The scene or image of a person pulling themselves out of a deep, dark pit only to look up and discover there’s still another ledge wall to climb. So the person catches their breath, gives themselves a second to collect their own thoughts, readies themselves, and begins the next climb knowing that this too shall be conquered.

The feeling of being on a busy highway, your car hits a patch of greasy road and it goes into a skid, but then you get the car under control. Your heart is racing but you feel like a badass for keeping the chaos in check.

And If pop music is a dish of assorted and unwrapped candy then prog metal is a Manhattan cocktail inside a locked safe.

You’ve mentioned YANNI and LORD BANE as influences. Which aspects of their music inspired you the most this time, and how do they surface in the album?

Yeah, LORD BANE was a huge musical influence on me. Just everything about ´Age Of Elegance´ got me excited when I was growing up and learning how to play. Especially the keyboards on that album. The keyboards weren’t doubling the guitars, they weren’t super busy, they weren’t these cliché sounds. If the guitars were going down in melody then the keyboards were going up; if the guitars were busy, then the keyboards were making these sweeping washes of sound. The keyboards on that album were just so unique. The vocals were phenomenal and the drums were so unique too with the incorporation of military snare lines here and there. It was just so cool.

Yanni’s always been huge influence to me as well. I started playing music on piano so, I have a soft spot for stuff like Yanni, Hania Rani, and Ludovico Einaudi. The biggest influence on me when it comes to Yanni and as it relates to metal was the songwriting and structure of the songs from his live albums. This was back when he altered a lot of his songs to work with a big live band during those ´Live At The Acropolis´ and ´Tribute´ shows. If you listen to those albums, you’ll hear just a ton of solos from so many different types of instruments and players from around the world. There are so many styles and textures thrown into those songs. It’s just really interesting to listen to. I still love those albums.

You can also hear how I use his musical motif hand-off tricks. I mentioned this before a bit earlier.

Let’s say there’s a bass solo which leads into the next musical part and melody. I noticed that sometimes a solo will end with a nod to the upcoming melody theme. It’s a beautiful trick of cohesion and patterns.

If you listen to ´Until The Dark Responds´ and the big section in that song with all the solos going off of each other, that’s a direct influence of Yanni.

If ´The World Outside´ could work as a “time machine” – which era, or which state of mind, would you want the listener to experience?

Hopefully it won’t be locked into an era. I’m sure some people would listen to it and say it might sound kind of 80s with the guitar work and all, but for me I would hope it would reside on its own. I would like to think people can still listen to this album 20 years from now and still feel that it sounds relevant.

As far as what state of mind, I think it can be best summed up in the very last minute of ´Where None Shall Follow´. The ending of that song, coming out of the chorus and all the heaviness and then ending on the beautiful piano and string part…. I would like to think that encapsulates the mood of the album. That feeling of having gone through something difficult and intense, to come out as a stronger person on the other side with a sense of hope and accomplishment.

After eleven years of work – were there musical ideas that didn’t make it onto the album, but that you still want to realize in the future?

Not really. All the parts and sections were written specifically for each song. By that, I mean, I didn’t have a bunch of riffs that I had left over. I wrote riffs and chords and melodies specifically for each song. Whatever new riffs that I might be working on now are for other things in the future.

Not only that, but when I was done writing music for ´The World Outside´ I actually moved on to other things. I was actually waiting for Keith Warman to record his guitar parts. So, while I waited around on him to do that, I started working on music for a couple of other projects. I’ve returned to those other projects to wrap them up. It won’t be CEA SERIN, but new band names and new projects basically under a new banner.

What does finishing this album mean to you personally – as a musician, as a composer, as a person?

I’ll tell you a story of how long these songs have been in my head waiting to finally be heard by others.

Back in 2004 I signed my first deal with “Heavencross Records” for Europe and “Nightmare Records” in the U.S. After I had signed those contracts I was talking to my mother about what was going on with all of it. She asked me what the name of our second album was going to be and I said, ´The World Outside´. So, that was back in 2004 that I knew this album was in the works. I had the earliest stages of the songs in development even way back then. I had the album title back then. So, yeah, a little over 20 years I have been pushing to get this album done.

January of 2025 I had just gotten fed up of waiting around for other people and decided to do it myself. Of course, Rory did all the drums and percussion but I decided to go ahead and finish up the record by recording guitars myself and outsourcing the solos to other people. It was a tough decision but a necessary one.

The day I mixed down all the individual tracks and turned them all over to Tom MacLean to do the final mix and master…that was the best night of sleep I had in two decades.

The album and the computer it was on had survived a flood. When my house was being flooded with several feet of river water I had made sure to save the computer and the backups. It was the most important thing to me to save.

I’m enormously proud of this album and when I die I would be happy if “Known for the album ´The World Outside´ by CEA SERIN” was on my tombstone. By that, I mean, if I die tomorrow at least I can say I finally saw this project to the end and it came out the way I wanted it to. It’s my proudest achievement and my favorite thing I’ve done…so far.

If someone listens to ´The World Outside´ again ten years from now – what would you want them to discover that they may not notice the first time?

Two things:

I had a friend once tell me his father had this idea that if a person listened to a piece of music and was able to hear every note and notice every detail, they would then have lost all interest in that piece of music from that point on. I don’t necessarily agree with that, but I do like the sentiment that a piece of music needs to offer the listener a depth of discovery which will offer receipts for years to come.

The second thing is that I saw a video on YouTube of someone who listed a few progressive metal albums that came out 20 years ago but still sound relevant today. Our first album was on that list.

So, I hope people listen to this album a decade from now, still discover new details and still think it sounds relevant and not era specific, i.e. not 80s or 90s sounding.

On top of that, I hope people will see and hear that the lyrical themes are still relevant and will always be relevant, i.e., the ideas portrayed about struggle, individuality, achieving goals, and carrying the light for others to see the way.

Each track on ´The World Outside´ feels like its own chapter. Is there a hidden dramaturgy that ties the pieces into a larger story?

No, each song is its own story, its own entity, and is not connected thematically with one another. The last three songs connect uninterruptedly but the lyrical themes are different. It’s certainly not a concept album like ´Operation: Mindcrime´ and not a concept album with an overarching connective tissue.

In fact, that’s kind of why I like having these longer intros to some songs to act as a palate cleanser from the last song they might’ve heard. It’s like the opening credits of the next movie.

Some songs seem to capture inner conflict, while others sound like departure and liberation. Does this reflect a personal journey, or a more universal experience?

All the songs are definitely derived from personal experience and observation but written in such a way to be more universal.

I certainly have my own take and experience with trying to go my own path as dealt with in ´Where None Shall Follow´. I’ve met and have emotional connections to the people who influenced the fame-seeking, instant gratification hounds within ´The Rose On The Ruin´. I have my own pursuits and interests and can see where I started out from and where I’m currently at as discussed in ´Until The Dark Responds´, but I can also see how it relates to humanity on a larger scale. And when it comes to ´All The Light That Shines´ and ´When The Wretched And The Brave Align´ I think we can all share our own experience and be able to relate to each other with our own stories regarding leading by example and how to handle conflict. Finally with ´Wisdom Of The Aging Fathers: Three Regards To Reason´, I’ve come across my own three father figures, learned from them, and feel like I’ve forged my own path thanks to their guidance and I think others will have their own similar journey with respect to that theme.

Is there a figure, a lyrical “I,” or a voice that runs throughout the album – or is each song a new perspective?

I don’t think there’s a lyrical “I” throughout the album. Maybe in a sense of there’s a single actor portraying different characters—to use a cinematic reference. It’s all the same person we know and recognize but the character they’re playing at this time is different. Or, maybe it’s like watching the evening news and we see all these different news stories. They’re all different stories, all different events, but all recognize the city or town they’re taking place in.

Certain passages feel almost like “inner monologues.” Did you deliberately think of music as a language of the subconscious?

I think maybe music is a response to the subconscious, a reaction to what the subconscious is coping with, or a translation of emotion into thought if that makes sense.

I know there have been many times where I’ve seen something, heard something, felt moved by something and then—with that internal emotion stirred up—some musical elements will crop up in my head.

I think it’s every musician’s duty to learn their instrument and their voice to such a degree so that they can manifest what they hear in their head when they’ve been stirred up like this.

If you had to pick one song as the “key” to the entire album – which would it be, and what does it reveal?

That would be ´Until The Dark Responds´ which directly relates to many of the themes throughout as well as the album artwork. It directly challenges how people may tell you the world outside is one way but if you take a look for yourself you will see that maybe people are trying to get you to think of things their way and not your own. With that being said, ´Until The Dark Responds´ is about living in this world with those around you trying to mislead you as you go about your goals and ambitions. It also could be a mirror to humanity’s evolution and a testament to how far we’ve come.

I think we should always fight for our goals, purpose, and ideals. No matter what anyone tells you. In life we will get knocked down, we will even get kicked while we’re down, we will get ridiculed and mocked. But there’s one truism I will always hold on to and that is the adage of “it’s not what they say, it’s what you know.”

Keeping getting back up. Because suffering is part of the journey. But it doesn’t define you. Being knocked down shouldn’t be adopted as your identity. What defines you is how you rise, and continue to rise, how you continue to push on forward despite the pain, despite the setbacks. Getting knocked down is a certainty. What matters is getting back up, keeping your dignity and your wits about you. Because the ones who reach their dreams aren’t the ones who never fail, they’re the ones who refuse to stay down. So keep going, keep fighting. Keep striving. Until your last breath and until the dark responds.

https://generationprog.bandcamp.com/album/the-world-outside

https://www.facebook.com/CeaSerinMusic

Pics: Jay Lamm